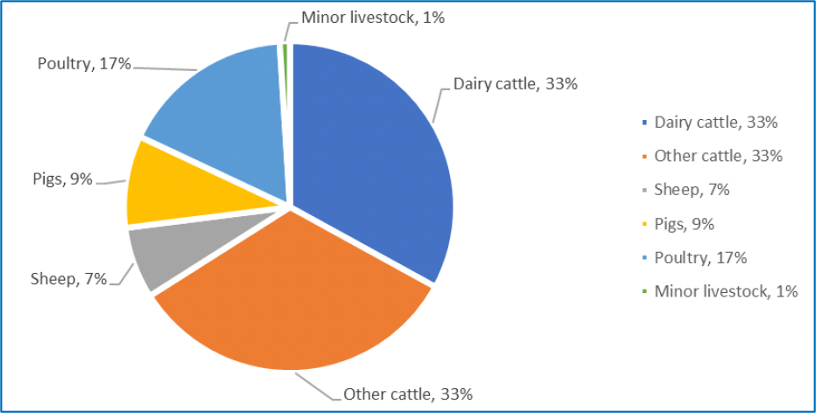

Intensive pig and poultry livestock units are facilities for the rearing of pigs and poultry, or for egg production. The resultant emissions to air from this industry are displayed in Table 1. The most prevalent pollutant from these systems in the UK is ammonia, which arises from manures, slurries and fertilisers. The agricultural industry accounts for around 90% of all ammonia emissions in Scotland[1], which can have detrimental impact on the environment. Figure 1 represents the emissions of ammonia from the livestock sector split into livestock categories for the UK. As shown poultry and pig represent 26% of all ammonia emissions.

Table 1: Emissions to air from the intensive rearing of poultry or pigs[2]

| Air | Production system |

| Ammonia (NH3) | Animal housing, manure storage, processing and land spreading |

| Odour | Animal housing, manure storage and land spreading |

| Dust (bioaerosols) | Animal housing, milling and grinding of feed, feed storage, solid manure storage and land spreading, heaters in buildings and small combustion installations |

| Methane (CH4) | Animal housing, storage of manure and manure processing |

| Nitrous oxide (N2O) | Animal housing, manure storage, processing and landscaping |

| NOx (NO+NO2) | Animal housing, manure storage and land spreading, heaters in buildings and small combustion installations |

| Carbon dioxide (CO2) | Animal housing, energy used for heating and transport on farm, and biogenic CO2 that may be emitted in the field |

Figure 1: UK emissions split by livestock category, 2020. Source: https://www.gov.scot/publications/environmental-authorisations-scotland-regulations-2018-proposed-amendments-consultation-draft-regulations/pages/3/

Ammonia emissions can lead to:

- plant damage

- impact the health of sensitive habitats, such as heathlands

- odour nuisance

- detrimental impact on human health[3]

To mitigate and reduce the environmental impact from intensive poultry and pig installations, they are regulated under The Pollution Prevention and Control (Scotland) Regulations 2012 (PPC 2012). These regulations, enforced by SEPA, focus on an integrated approach to environmental protection utilising Best Available Techniques (BAT) to prevent and minimise emissions.

[1] https://www.gov.scot/publications/cleaner-air-scotland-2-towards-better-place-everyone/pages/10/

[2] Table sourced from European Commission (2017) Best Available Techniques (BAT) Reference Document for the Intensive Rearing of Poultry or Pigs.https://eippcb.jrc.ec.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2019-11/JRC107189_IRPP_Bref_2017_published.pdf

[3] When mixed with other pollutants.

Installations rearing pigs and poultry that exceed the following thresholds are subject to control under PPC 2012 and are required to apply to SEPA for a PPC permit:

*©craigstephen

The 2017 Best Available Techniques (BAT) Reference Document (BREF) and associated BAT Conclusions define the standards that permitted installations must meet in order to comply with PPC 2012. The BREF also states the BAT Associated Emission Levels for ammonia emissions to air, nitrogen and phosphorous excretions.

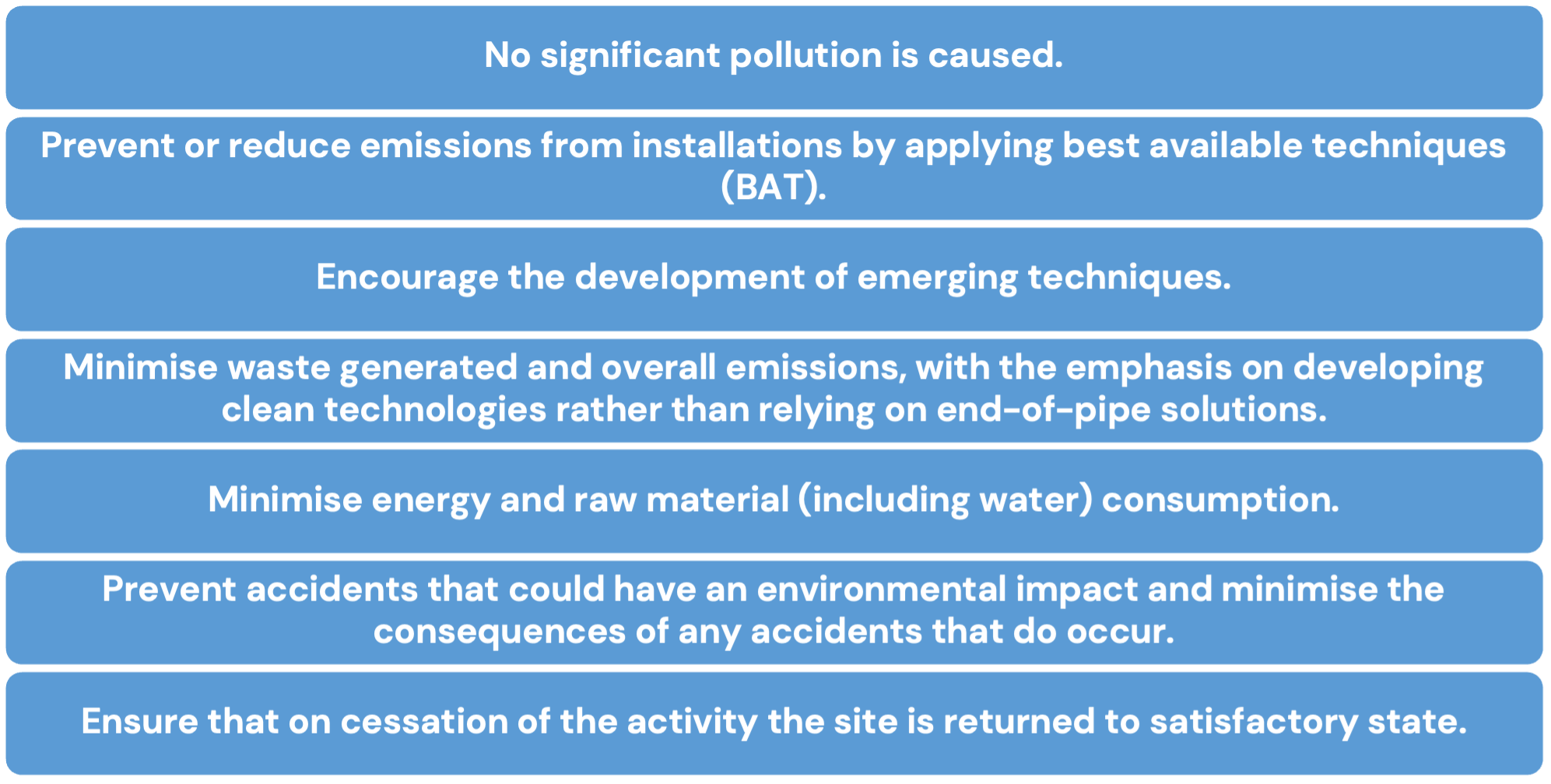

SEPA have produced a Pollution Prevention and Control (Scotland) Regulations 2012 (PPC) Intensive Livestock Installations: Standard Farming Installations Rules (How to Comply)[4] guide for farmers to ensure that they comply with the correct regulations with regard to intensive agriculture (note this was produced prior to 2017 BAT Conclusions). A PPC permit, once granted, places legally binding conditions on the operation of the installation to ensure that the principles listed below are achieved:

Designated habitats and sensitive ecosystems

Any new or substantially changed PPC pig and poultry installations will need to assess the potential impacts on designated sites (Special Areas of Conservation (SAC), Special Protection Areas (SPA), Ramsar Sites, and Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI)) from atmospheric emissions of ammonia. Where Likely Significant Effect on any SAC or SPA/ Ramsar and/or Likely Damage to the natural features of any SSSI cannot be ruled out, NatureScot will be consulted.

[4] https://www.sepa.org.uk/media/162852/sepa-s-standard-farming-installation-rules-how-to-comply-incorporating-ppc-application-guidance.pdf

Ammonia is a key air pollutant that can have significant effects on both human health and the environment. Ammonia emissions from agriculture not only represent the loss of a valuable nutrient but can also cause the following detrimental effects to the environment:

- Acidification of the soil through deposition of ammonia and transformation to ammonium and then nitrate; and

- Addition of nitrogen by deposition to areas of high nature conservation value or sensitive species, which may result in vegetation changes or increased nitrate leaching.

- Increased nutrient enrichment of watercourses and diffuse pollution.

Ammonia losses are considerably higher from manures and slurries containing a high ammonium nitrogen content e.g. pig slurry and poultry litter and manure.. Table 2 illustrates the various sources of ammonia emissions from poultry and pig units.

Table 2: Overview of processes and factors involved in ammonia release from animal houses[5]

| Processes | Nitrogen components and appearance | Affecting factors |

| Faeces production | Uric acid/urea (70%) + undigested proteins (30%) | Animal and feed |

| Degradation | Ammonia/ammonium in manure | Process conditions of manure e.g. T, pH, Aw, airflow at floor level, urease activity |

| Volatilisation | Ammonia in air | Process conditions, local climate, exposed surface and contact time of manure/slurry with the air |

| Removal | Ammonia in animal house | Ventilation: T, RH, air velocity |

| Emission | Ammonia in environment | Air cleaning |

| NB: T=temperature, pH=acidity, Aw=water activity, RH=relative humidity. | ||

[5] Table sourced from European Commission (2017) Best Available Techniques (BAT) Reference Document for the Intensive Rearing of Poultry or Pigs.https://eippcb.jrc.ec.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2019-11/JRC107189_IRPP_Bref_2017_published.pdf

Several techniques can be used to reduce ammonia emissions from buildings and slurry and manures stores, including:

- Slurry stores should be covered, if this is safe and practical, which will also help to reduce levels of waste production by excluding rainfall.

- If covers are not practical, frequently moving slurry to a covered store.

- Slurry cooling systems

- Additives can be added to stored manure to manipulate the pH value.

- Techniques can be employed to encourage fast air drying of manure or litter in poultry houses.

- Investing in heat exchange systems in broiler houses.

- Using air scrubbers in buildings.

- Good animal health maintained, buildings kept dry, clean and suitably ventilated.

Ammonia emissions are more concentrated and harmful at source, with the impact to the environment reducing further from source. Therefore, the impact to the surrounding environment and the potential damage should be mitigated in the first instance. By incorporating Best Practice Techniques (BAT) you can reduce the likelihood of emissions, additionally it can be beneficial to plant vegetation around the source to help absorb ammonia emissions from the surrounding environment. The planting of tree belts around livestock units can therefore help, along with BAT, to reduce the impact from ammonia emissions on the environment.

The handling and storage of manure and slurry on the installation will be controlled via the PPC permit. The spreading of manures, litter and slurry out with the installation boundary is controlled by CAR General Binding Rule 18. Information on slurry and manure can be found here.

SEPA regulate odour, noise and dust from PPC installations by permit conditions and the use of Best Available Techniques (BAT). Local authorities also have the power to act on complaints arising from agricultural activities under the nuisance provisions of the Environmental Protection Act 1990 (EPA). Using the EPA, an abatement notice may be served requiring a decrease of the nuisance or prohibiting or restricting its reoccurrence.

The use of appropriate practices allied to good planning and management of both new and existing installations can help minimise the risk of causing odour, noise or dust. The aim is to contain the emission within the installation boundary by reducing emissions at source.

There is growing concern around the impact of very small dust particles (Particulate matter (PM10)) on human health. Standards have been specified to reduce the risks to an acceptable and very low level in the Air Quality Standards (Scotland) Regulations 2010. This is based on the current understanding of health effects and exposure to air pollutants outlined in the national air quality strategy; Cleaner Air for Scotland 2. PM10 levels will vary due to numerous factors including:

- climatic variables,

- number of birds,

- ventilation system used,

- management practices, and

- distance from the site.

Generally speaking, the potential concentration will decrease with distance from the source, therefore, the further away the sensitive receptor, the less impacted it is expected to be. Receptors close to large poultry farms will likely need further assessments and modelling to determine impact, however, there can be errors and difficulties accurately modelling emissions very close to the source.

Defra Local Air Quality Management Technical Guidance (TG22) (August 2022) sets out screening assessment criteria for poultry farms and includes a distance for sensitive receptors from the site for PM10 emissions. Exposure within 100 m of an intensive poultry unit is one of their screening criteria that will likely require monitoring or dispersion modelling to determine if there will be any adverse impacts on human health.

Current guidance states: Screening assessment 400,000 birds (if mechanically ventilated) / 200,000 birds (if naturally ventilated) / 100,000 birds (if turkey unit) – Exposure within 100 m from the poultry units. If any of these criteria are met, carry out monitoring survey/dispersion modelling. Please note that the distance from receptors requiring modelling with vary from site depending on the requirements of the planning conditions and the receptors involved.

Odour can be a statutory nuisance or a breach of permit condition and needs to be mitigated. You need to be vigilant and carryout regular inspections around your installation to ensure that mitigation measures are working to reduce odour to the surrounding environment. If you receive complaints regarding odours from your installation you will need to act.

An important factor with odours is determining at what concentrations odours will be regarded as objectionable. When determining criteria for assessing the likelihood of nuisance, consideration should be given to the nature of the odour in relation to the environment in which it will be found. It is reasonable to expect that higher strengths of agricultural odours would be tolerated in a rural environment than would be the case if they were encountered in an urban environment. Whether or not odour emissions amount to serious pollution depends on a number of factors including personal perception. There is no single or easy method of reliably measuring or assessing odour pollution and any conclusion is best based on a number of, often subjective, factors.

The concept of ‘FIDOL’[6] is sometimes applied in an attempt to determine the main factors that affect the degree of odour pollution, these are:

- Frequency of detection;

- Intensity as perceived;

- Duration of exposure;

- Offensiveness; and

- Location

If complaints have been made you may be inspected and will need to produce evidence that you have put in measures to reduce odour from source. An odour management plan must be in place to ensure that odour is managed and maintained throughout the unit.

[6] Note FIDOL is sometimes also referred to as FIDOR, where the final letter of the acronym relates to receptor

Noise can be classed as a statutory nuisance if it either:

- Unreasonably and substantially interferes with the user or enjoyment of a home or other premises.

- Injuries health or is likely or injure health

If noise is deemed to be classed as a nuisance you will need to assess the impact and demonstrate that Best Available Techniques (BAT) will/are being used. SEPA have produced Noise: Summary guidance tor Pollution Prevention and Control (PPC) applications guidance to help ensure noise is monitored and reported correctly. As part of the BAT’s you must develop a noise management plan (NMP). NPM must demonstrate that you are committed to reducing noise pollution and that you understand the risk and have planned a mitigation strategy. A NMP should be reviewed regularly, suggested biannually. As a minimum a NMP should include:

- a clear statement that you understand and accept your responsibilities for controlling noise impact, and that you will regularly review the effectiveness of your NMP;

- a commitment that either you, or your contractors or subcontractors, will make sure that any noise control equipment is designed, operated and maintained appropriately so it controls noise effectively at all times;

- a risk assessment of noise problems from normal and abnormal situations (including worst case scenarios due to, for example, weather, temperature, or breakdowns, and accidents)

- details of the appropriate controls (both physical and management) needed to manage the identified risks;

- confirmation of the level of monitoring that should be in place;

- details of the actions you will take, contingencies, and responsibilities when problems arise (it is particularly important that you include expected actions resulting from exceptional circumstances or where serious pollution may occur);

- confirmation of the procedures in place to consider reducing or stopping operations to avoid serious noise pollution; and

- a procedure for engaging with neighbours to minimise their concerns and respond to complaints.

More information can be found within Guidance – Noise and vibration management: environmental permits.

Minimising odour from livestock buildings

When designing new buildings, consider their siting in relation to residential accommodation, and avoid siting installations within 400 m of residential areas. Where possible, locations downwind of residential areas should be chosen. Ensure buildings are properly ventilated to control temperature, humidity and the concentration of gases, and to provide a good distribution of clean air under a wide variety of external weather conditions. Ventilators should be thoroughly cleaned between batches of stock and maintained to ensure operation at the correct airflow for the stock requirements. The removal of dust will help to reduce the level of odour. Humid conditions caused by poor ventilation result in odours and the build-up of high levels of ammonia.

Professional advice should be sought on the positioning of ventilator outlets. The higher the outlet, the greater the dilution factor from air movement. Ventilation outlets positioned along the sides of buildings, below slatted floors and immediately over slurry collection channels can result in poorer dispersion of odours. The use of bioscrubbers, biofilters and tall chimneys as exhaust ventilators for odour removal can be effective technologies, but they are expensive and it is generally better to control odours at source.

To control odour, it is essential to maintain a high standard of hygiene and cleanliness:

- Plan the collection and storage of slurry and manure;

- Minimise open concrete areas used for livestock. Drainage arising from this area must drain to the slurry storage system. It should not be allowed to run off on to roads where pollution can result, and there would be potential increase resultant odours;

- Maintain or replace drinking systems to avoid overflow and spillage, which leads to wet, smelly areas, increased levels of waste production, slurry dilution or wet poultry litter or bedding;

- Utilise multistage feeding systems to prevent nitrogen losses;

- Maintain dry friable litter and fast air drying or manure or litter. However, ensure that this does not resulting in increased dusty conditions if too dry;

- Clean livestock buildings regularly and thoroughly using the correct type and quantity of disinfectant and volumes of wash water;

- Ensure that all cleaning material/drainage water is collected. Never discharge wash waters to watercourses as there can be resultant odour. Contact SEPA for advice on suitable disposal arrangements; and

- Comply with the stocking density recommendations set out in the appropriate Codes of Practice for the Welfare of Livestock[7]. Further advice on this can be obtained from Scottish Executive Animal Health Offices.

[7] https://www.gov.scot/policies/animal-health-welfare/animal-welfare/

SEPA Pollution prevention and control https://www.sepa.org.uk/regulations/pollution-prevention-and-control/

SEPA Best Available Techniques (BAT) https://www.sepa.org.uk/regulations/pollution-prevention-and-control/best-available-techniques-bat-reference-documents-brefs/

UK Air Pollution Information System https://www.apis.ac.uk/

Simple Calculations of Atmospheric Impacts Limits http://www.scail.ceh.ac.uk/

NetRegs – Prevent odour nuisances from your farm https://www.netregs.org.uk/environmental-topics/nuisances/nuisance-from-dust-insects-noise-odour-and-pathogens/prevent-odour-nuisances-from-your-farm/

Scottish Government Pollution: Noise and nuisance https://www.gov.scot/policies/pollution/noise-nuisance/

Air Quality in Scotland https://www.scottishairquality.scot/

Related resources

Integrated Pest Management and the Voluntary Initiative

How can you improve pesticide management on farm?

How can you improve pesticide management on farm? In this podcast we chat with Neal…

Environmental and animal welfare considerations of dealing with sheep scab

This podcast focuses on how farmers can manage sheep scab. In particular discussing what farmers need to be aware of and the rules and regulations that need to be followed when managing sheep dip from animal welfare, to environmental regulation. Photo credit: ©Neil Fell